Great Scott!

|

It’s likely that everyone has encountered a work of fiction involving an extra dimension at some point. Be it time travel or trans dimensional beings, “extra dimensions” is a very popular topic. But what does it actually mean?

The Basics

If I was asked the question “What is a dimension?” I would say “A place for a number to go in a coordinate”. That is, if I was to give a coordinate of a point in a particular space, for each dimension that space has, I would need to specify one number. In a one dimensional space (think an infinitely long line), to specify any point, I need only one number, and that will tell you how far along the line my point is. In a two dimensional space (Super Mario), I can move (say) up/down and left/right, so I need to specify two numbers. Similarly, to specify a point in three dimensional space, I need three numbers. Imagine a space where you would need four numbers to specify a point. It’s very easy to imagine spaces with up to three dimensions, but due to the nature of our universe, we are not accustomed to go any higher than that.

What about time?

Time can be considered a dimension, and it’s possibly the easiest way to imagine a fourth dimension. To specify a point in the universe at a particular time, we need three numbers to specify the point (as it is a 3D space) and a fourth number to specify the time. Thinking of time as a dimension is a convenient way to help understand a fourth geometric dimension, by thinking of a three dimensional space inside the four dimensional space changing as the fourth axis is traversed. That last sentence was a bit intense, but should become clearer to you in the course of, well, time.

Analogy Time!

Imagine a pen, with an infinitely small point. If you draw an infinitely small dot on a page, we could say that the dot has zero dimensions. Now, with the pen, draw a straight horizontal line on the page. The line has one dimension. Now imagine grabbing the line and pulling it down the page, forming a square. Now take the square, and pull it up, out of the page, and you get a cube. Now what? We can go no further in a three dimensional space. So what does the cube become?

Imagine living in a two dimensional world. Suppose we inhabited a large sheet of flat paper. Three dimensional beings might take a cube, and push it through our world. Initially, there would be just some empty space. Then, depending on how they push the cube, we might suddenly see a square appear, or a rectangle, or a triangle. We would continue to see a two dimensional cross section of the cube until it completely passed through our world and vanished. If four dimensional beings want to push a four dimensional shape through our three dimensional universe, we would only be able to see a single three dimensional cross section at a time.

If you get a whole bunch of cut-out square pieces of paper and stack them together, you can make a cube. You are creating a 3D shape by stacking 2D shapes in a third dimension. Now say you had a whole bunch of cubes. You can’t stack these like you did the squares to enter a new dimension, but you can “stack” them through a fourth dimension. At any point, you can only see one of them. Think of our 3D universe as a cross section of a 4D universe containing our “stack” of cubes. We can re-position our universe on the stack (as you could re-position a 2D plane making a cross section with a cube to obtain a non-square cross section). At each new position, we might see a cube. If we went too far in the new dimension, we would go “off the edge” and see nothing. If we rotated our universe (as you might tilt the paper to get a rectangle or triangle), you would see something else.

One more. You learn to draw prisms by drawing a 2D shape and projecting lines off its vertices to create a 3D shape. If you draw a square and project lines from each corner, you can draw a cube. At the end of each line is a vertex of a second square, located in a different 2D plane of the 3D space. Although you’re drawing on a two dimensional surface, you imagine these lines as being projected in a third dimension to create an image of a 3D shape. So take a cube, and from each vertex, project a line through a new, fourth dimension. At the end of each line is a vertex of a second cube, located in a different 3D space of the 4D “hyperspace”.

An Example

Continuing from the last analogy, suppose, rather than projecting from each point to points on a second identical cube, we project to a smaller cube. This is the four dimensional equivalent of a square frustum. I guess we could call it a cubic frustum. Now, if this cubic frustum was to pass through our universe, starting with the larger “end”, we would first see a large cube appear. The cube would gradually shrink, and eventually vanish. If, on the other hand, the frustum passed through slightly crookedly, we would see a pyramid which grew into a distorted cube-like shape which got smaller and smaller and eventually turned into a pyramid and then disappeared. This also demonstrates how thinking of the 4th dimension as time can help us visualize four dimensional shapes.

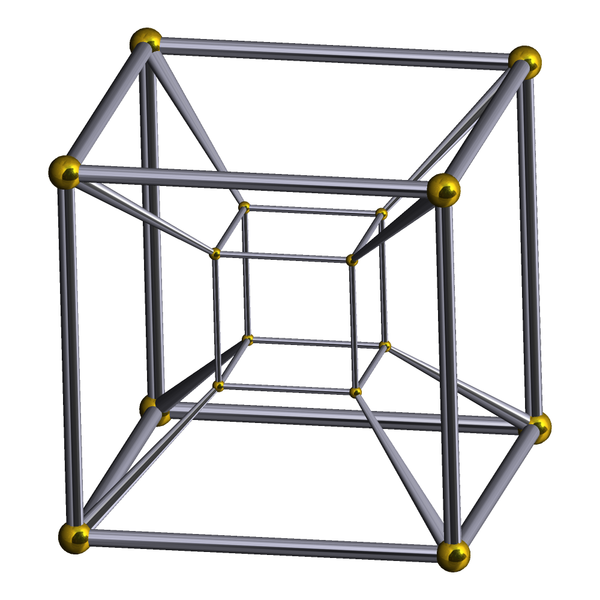

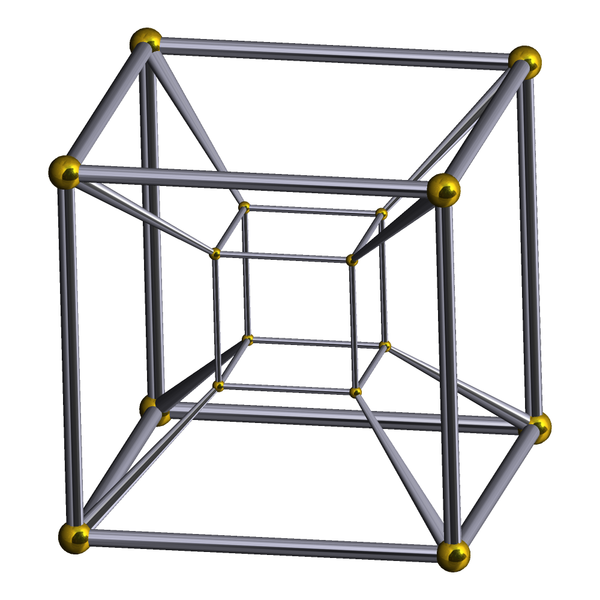

The common image of a tesseract

|

The Tesseract

Here is a demo. Use WASD to move, left/right to turn, and play with the number keys and “-”/“=” keys to rotate it.

A tesseract is the next progression in the “point, line, square, cube” sequence. It is a four dimensional shape obtained by projecting lines from a cube through a fourth dimension. I said that in our 3D universe we can only see 3D “cross sections” of 4D shapes, so you should be asking yourself “Why does a tesseract look like a small cube inside a big cube?”.

Here’s a quick story about how I learnt the answer to that question. The tesseract demo was initially intended to be a 4D shape exploring demo. It would display a 3D cross section of a 4D shape, and let users move around in four dimensions. Here is said demo. It has the same controls as the tesseract demo, and i/k moves in the fourth dimension. The 4D shape in the demo is a “cube based hyper-hourglass”. That is, a cube projected to an inverse cube, so the centre is a single point.

But I digress. I was working on that app, and got it to the stage it’s currently at. I’d been reading some literature on 4D shapes, and I’ve read about tesseracts in the past, and whenever you see an article about tesseracts, you see the picture of the little cube inside the big cube. Until now, I never really understood why it’s drawn like that. It’s a 4D shape, how can they even fit the whole thing in a 3D space, and why draw it like that.

But it’s actually really simple. Let’s step things down a notch. Look at a picture of a cube, drawn on paper. The cube is 3D, but the image is 2D. Also, if you look at the cube from the right angle, it looks like a small square inside a big square. The difference in the size of squares is because of perspective. Things in the distance look smaller. Now, in the case of the tesseract, perspective is working in another dimension. When you look at the small cube in the big cube, the inside cube isn’t actually smaller, it’s just further away. It’s further way in the fourth dimension.

That was the epiphany that lead to me being able to create the tesseract demo. I already had the framework in place to convert 4D shapes into 4D shapes by taking cross sections. It was a simple modification to convert 4D shapes into 3D shapes using projection.

The Demos

I have already written a 3D engine in javascript. In fact I have written several, but the most advanced one is this. A 3D engine takes a description of a 3D environment and converts it into a 2D image which can be displayed on a screen. The aim of this project was to display a 4D image on a screen. It was easiest to write a program that converts a 4D environment into a 3D environment, and let my 3D engine to the rest of the work. So that’s what I did. The interesting part is how I convert a 4D environment into a 3D environment. For this demo, I used cross sections. The 3D to 2D analog is using a plane to cut a 3D shape, then displaying the cross section of the plane and the shape on the screen. I take a 3D cross section of a 4D shape, and hand the result to my 3D engine.

The difference between this and the hyperspace demo is the way it converts a 4D shape into a 3D shape. Rather than taking cross sections, this demo uses perspective projection. I multiply every vector describing a vertex by the reciprocal of the distance from that vertex to the viewing position in the fourth dimension only. This is why things further away in that dimension appear smaller. The entire 4D shape is draw inside the 3D space in the same way as a 3D scene can be drawn on a 2D canvas.

Philosophy Time!

Back to the idea of thinking of the fourth dimension as time. The universe progresses over time, according to the laws of physics. Ultimately, this bring about changes of state over time. A tree will grow, a mountain will erode, a person will age. A model could be proposed where an object’s existence was mapped out in a fourth dimension. Each 3D cross section of the object represents the object at some point in the course of its existence. Over time, we are just progressing along the 4th axis at some rate, and so the 3D cross section we perceive of the 4D universe we occupy is constantly changing.

Vertices, Edges, Faces, ???

A point can be thought of as a vertex. A line has two end points which we could consider vertices, and the line itself could be considered an edge. A square has vertices and edges, and the square itself could be considered a face. A cube has vertices, edges and faces.

What about a tesseract? A cube has 8 vertices, and since a tesseract is obtained by connecting two cubes, it has 16 vertices. A cube has 12 edges. The tesseract has two cubes worth of edges, and an additional edge for each vertex of a single cube, which are used to attach the two cubes, so a tesseract has 32 edges. A tesseract has 2 cubes worth of faces, plus an additional face for each edge of a single cube, which connect the corresponding edges in each cube, so 24 faces.

Say I represent a tesseract by specifying its vertices, edges and faces (which is exactly what I do in my demos). If I take a 3D cross section of it, at any point apart from its ends, I will only get a 1D cross section of its faces. Each of its faces can be considered a subset of a 2D plane, which may or may not lie inside a given 3D space. The possibilities are the plane is parallel to the space, and doesn’t enter it at all, it’s parallel to the space and lies inside the space (the only case in which the entire face is visible as a 2D entity), or the plane intersects the space along a line. The third case is the one which occurs in the middle of a tesseract represented with vertices, edges and faces. The 1D cross sections of the 2D faces which connect each edge of the first cube to the corresponding edge of the second cube forms a wireframe cube, which is why in the hyperspace demo, before any rotations, the you see a wireframe cube.

But what if I want to see a cube with faces at any point along the teserract. If a tesseract was to pass through our universe, surely we would see a solid cube, and not just a wireframe. But how would we make it so that a cross section of a tesseract has actual faces? In addition to the vertices, edges and faces, we need something else in our tesseract representation. Let’s introduce the “hyper-face”. This is actually just a 3D solid. In this case it is a cube. 6 cubes to be precise. For each face of the first cube making up the tesseract, there is a hyper-face (cube) with that face as one of its faces. Its face on the opposite end is the corresponding face of the other cube making up the tesseract. Its other faces are those connecting the corresponding edges of each cube which surround its two existing faces. The cross sections of these hyper-faces are 2D faces, which lie in the right places such that the 3D cross section of a tesseract defined with hyper-faces is a cube with 2D faces.